In its “Fast distributions and slow servers” article, Joe ‘Zonker’ Brockmeier explains the difficulties that Fedora has to use its own distribution on their infrastructure and echoes some questions they faced:

In its “Fast distributions and slow servers” article, Joe ‘Zonker’ Brockmeier explains the difficulties that Fedora has to use its own distribution on their infrastructure and echoes some questions they faced:

Why wouldn’t a Linux distribution project wish to showcase the distribution by hosting its infrastructure using its own system?

I completely share the underlying assumption. Eating its own dog food is very important if you want to build a Linux distribution and claim with some confidence that it’s of quality and usable.

Debian does quite well nowadays in that respect.

There were times where the mailing list server was using Qmail (non-free at that time, and thus not part of Debian) but that’s long gone. We have also seen our build infrastructure relying on software that was not public and not packaged in Debian, but that also is history.

The Debian System Administration team (DSA) maintains more than 140 servers running Debian. They mostly run the stable version of Debian but a few test machines are already running Squeeze since a few months (qa.debian.org for example). The Debian admins want to ensure that the next stable release of Debian still has everything they need and that the software they use still work as expected.

Big kudos to the DSA team for this choice! I hope we’ll be able to continue to live up to those standards for a long time to come.

PS: If you want to learn more about the setup that the DSA team uses, head to dsa.debian.org. You’ll find all their repositories and some of their internal documentation.

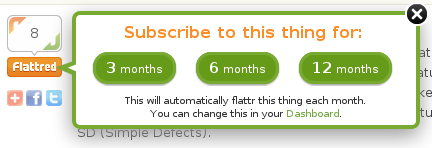

I put 5 EUR in

I put 5 EUR in