The Debian archive is known to be one of the largest software collections available in the free software world. With more than 16,000 source packages and 30,000 binary packages, users sometimes have trouble finding packages that are relevant to them. Debian developer Enrico Zini has been working on infrastructure to solve this problem. During the recent mini-debconf Paris, Enrico gave a talk presenting what he has been working on in the last few years, which “hasn’t gotten yet the attention it deserves”.

Enrico is known in the Debian community for the introduction of debtags, a system used to classify all packages using facets. Each facet describes a specific kind of property: type of user-interface, programming language it’s written in, type of document manipulated, purpose of the software, etc. His most recent work builds on that. It is available in Debian and Ubuntu in the apt-xapian-index package. Its purpose is to allow advanced queries over the database of available packages.

Users of apt-xapian-index

He started by presenting some early users of the infrastructure. The most widely know is Ubuntu’s software center. Its search feature provides results almost instantly thanks to apt-xapian-index. But it is a very simple interface that doesn’t exploit many of the advanced features provided by the apt-xapian-index.

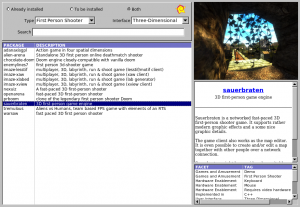

Another early adopter, making use of some more advanced features, is GoPlay!. It’s a graphical user interface to find games. It makes use of debtags to classify games so that you can browse, for example, all 3D action/arcade games related to cars. GoPlay has even been extended to be a more generic debtags based package browser and the package now also provides GoLearn!, GoAdmin!, GoNet!, GoOffice!, GoSafe!, and GoWeb!.

Fuss-launcher is an application launcher and not a package browser, but by using apt-xapian-index, it’s able to reuse information provided at the package level to make it easier to find installed applications. Package descriptions tend to be more verbose than those embedded in .desktop files. Enrico also showed another nice feature to the audience: if you drag a document onto its window, it will show you a list of applications that can open it.

Last but not least, apt-xapian-index provides a command line search tool that is vastly superior to the traditional apt-cache search: it’s axi-cache search (axi stands for apt-xapian-index). Enrico compared the output of a search on the letter “r”. While apt-cache spits out an infinite list of packages containing this letter somewhere in the description, axi-cache only listed packages related to GNU R. He also demonstrated the contextual tab completion. It makes it easy to use debtags and to refine your search. Once you have typed a first keyword, the tab-completion for the second one only contains keywords or debtags that are actually able to provide more restrictive results. Advanced queries with logical operations (AND, OR, NOT, XOR) are also supported.

Features of the backend

Enrico then dived into the internals. Xapian’s search engine is at the root of this infrastructure. He likes it because it’s a simple library (i.e. no daemon) and it has nice Python bindings. While apt-xapian-index’s core work is to index the descriptions of all the packages, it actually stores much more and can be easily extended with plugins (written in Python).

For instance, the information stored encompasses:

- words appearing in the description of the packages (including the translated descriptions if the user uses a non-English locale);

- their origin;

- their section;

- their size and installed size;

- the time they have been first seen;

- icons, categories, descriptions from the .desktop files they contain (through app-install-data);

- aliases for names of some popular applications that are not available on Linux (for instance “excel” maps to the debtag office::spreadsheet).

He already has plans to store more: adding popularity contest data (see wishlist bugs #602180 and #602182) will make it possible to sort query results in a useful way. The most widely used applications are good choices when it comes to community support, and they are likely of better quality due to the larger user base. Adding timestamps of the last installation/upgrade/removal, will make it easier to pin-point a regression to a specific package update.

The generated index is world-readable and can be used from any application provided it can use the Xapian library—which is written in C++ but has bindings for Perl, Python, PHP, Java, Tcl, C#, and Ruby.

Call for experimentation

Enrico believes that many useful applications have yet to be invented on top of apt-xapian-index’s features. He’s calling for experimentation and asking for new ideas. The only practical limit that he has encountered is the size of the index: currently it varies between 50 Mb (Debian unstable without translation) and 70 Mb (Debian stable/testing/unstable with one translation). He would like it to not grow over 100 Mb since it’s installed by default (due to aptitude recommending it) and he’s not comfortable with the idea of using more than 20% of the disk footprint of a basic install just for this service. That’s why the index was configured to not store the position of the terms: it’s thus not possible to find out packages whose description contains the word “statistical” immediately followed by the word “computing”. You can however find those which have both terms somewhere in their description.

Enrico wondered if apt-xapian-index offers too much freedom. That could explain why few people experimented with it despite his numerous blog posts with code samples and information on how to get started using it. But it’s not difficult to imagine use cases for this data. It could be used to extend tools like rc-alert or wnpp-alert, for example. They provide a long list of Debian packages that are looking for some help and are installed on the machine. With apt-xapian-index, it would be possible to restrict the results to the set of packages written in a specific programming language or for a particular desktop environment.

The more likely explanation is that too few people know about the tool. There are many more itches to scratch where apt-xapian-index’s features could be very useful, and my guess is that Enrico’s wishes will eventually come true.

This article was first published in Linux Weekly News. Click here to subscribe to my newsletter and keep up with the Debian/Ubuntu news thanks to my monthly digest.

I have been asked how Ubuntu relates to Debian, and how packages flow from one to the other. So here’s my attempt at clarifying the whole picture.

I have been asked how Ubuntu relates to Debian, and how packages flow from one to the other. So here’s my attempt at clarifying the whole picture. Most Debian packages are managed with a version control system (VCS) like git, subversion, bazaar or mercurial. The

Most Debian packages are managed with a version control system (VCS) like git, subversion, bazaar or mercurial. The