While preparing for the upcoming mini-debconf Paris, I noticed that we don’t have any good presentation template for OpenOffice.org Impress. I spent a few hours browsing Debian presentations put online by many speakers and was unable to find one that would suit me.

While preparing for the upcoming mini-debconf Paris, I noticed that we don’t have any good presentation template for OpenOffice.org Impress. I spent a few hours browsing Debian presentations put online by many speakers and was unable to find one that would suit me.

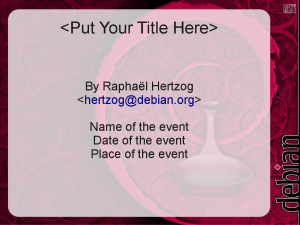

This situation was clearly unacceptable and I decided to spend a few hours to fix this. I selected a very nice wallpaper created by Alexis Younes, used The Gimp to add a translucent white box so that the text can still be read, and combined all this in a OpenOffice.org Impress template.

Click here to download the template. You can also get the Gimp XCF file for the background image.

By the way, the same wallpaper has been used by Sam Hocevar to create nice-looking Debian business cards.

PS: I contacted Alexis Younes by mail and he agreed to put the wallpapers under GPL-2+. It has been clarified on his webpage.

PPS: Given that the selected background image is inspired by Debian’s restricted use logo, this template should only be used by official Debian members.

I launched

I launched  While I have spent countless hours working on the new source format known as “3.0 (quilt)”, I’ve just realized that I have never blogged about its features and the reasons that lead me to work on it. Let’s fix this.

While I have spent countless hours working on the new source format known as “3.0 (quilt)”, I’ve just realized that I have never blogged about its features and the reasons that lead me to work on it. Let’s fix this.